If you wanted to understand why flipping through Stacy Kranitz’s recent photography book, As It Was Give(n) to Me, feels like plunging your head into ice water, you could ponder the omission of captions that might have contextualized her images of Appalachia. You could dwell on the dissonant chord struck by mixing beauty pageants, burning cars, and bloody teeth together on the page.

Or you could consider a moment in January 1944, when a lanky Kentucky soldier disembarked from a requisitioned passenger ship and stepped foot for the first time in French-mandate Morocco.

“The Arabs were a never failing source of amazement,” Harry Caudill wrote, recording his impressions in a column for his hometown newspaper, Whitesburg, Kentucky’s Mountain Eagle. “Most of the men carry long keen knives beneath their robes, and one would doubtless stab at his brother for a pair of shoes,” he continued. “They are indescribably filthy.”

Though his regiment eventually deployed to Italy, Caudill chose to focus a significant portion of his column on his peregrinations in Casablanca. Other soldiers had written about the battlefields of Europe; Caudill could claim a niche by representing Morocco, at least as he imagined it. His descriptions—of wily men and their hordes of veiled wives, of a constant chorus of braying donkeys and mournful flute notes—evoke the tropes of what Edward Said would later call “Orientalism.” Never mind that few of his details withstand serious factual scrutiny; Caudill could define Morocco and its people for the readers of The Mountain Eagle however he pleased.

After the war, Caudill returned to Kentucky and finished a law degree. Years later, he resumed writing, now about an area closer to home: Appalachia. His work, published in The Atlantic and in a series of best-selling books, forced the United States to pay attention to the region, and established Caudill as its unofficial spokesperson. In his reports from Appalachia, Caudill adopted the same authoritative tone and looseness with facts that he had wielded in his writing on Morocco; this time, though, it was his own neighbors whom he cast as exotic.

These days, Caudill is less of a household name than he once was, but his portrayal of Appalachia has stuck. Journalists and photographers flooded into the region in the 1960s, drawn in part by his writing. The photos and news segments they mined from the mountains galvanized efforts to improve standards of living across the United States—but they also ingrained in the American imagination an understanding of Appalachia as a poverty-stricken backwater. The widespread acceptance of Caudill’s representation had a redemptive effect for the rest of the country: Americans could congratulate themselves on their relative tolerance and sophistication by viewing Appalachia with both pity and disgust, treating it as impoverished and backward, racist and regressive.

In As It Was Give(n) to Me, Kranitz consciously tangles with the image Caudill constructed. The book’s title calls attention to both the power of stereotypes (the myth, as it was given to me) and the demand for something deeper (as it actually was, give it to me). Kranitz’s photographs—of a man throwing a chair at his home, of coal trains, cross burnings, and cloud-shrouded hills—are too discordant to offer a coherent alternate narrative. Instead, her work takes aim at the act of narrative construction itself.

Kranitz was born in Kentucky and grew up in California and Florida; she isn’t, strictly speaking, “Appalachian.” She arrived in the region in 2009 to work as a photojournalist but quickly grew frustrated with how she saw it depicted in news coverage. She decided to stay, settling in a small town in Tennessee, just on Appalachia’s official borders.

But you don’t really need to know her biography to understand her work. The person she’d much rather talk about is Harry Caudill.

It all began in a dreary coal-camp schoolhouse, just northeast of Whitesburg.

By 1960, Harry Caudill was a well-established lawyer in eastern Kentucky, and he had been invited to deliver an address to the graduating eighth graders of Millstone Creek. By Caudill’s telling, a mining accident had left one child orphaned, and the parents of three other children were jobless. As rain streamed through gaps in the roof, the students performed a glum rendition of “America the Beautiful.”

Caudill came home furious. He paced his living room, ranting to his wife, Anne, about how his region had fallen into poverty. Anne sat down at her typewriter and began to transcribe. Soon they had a manuscript.

World War II had fueled an unprecedented demand for coal, and Caudill had returned from military service to a thriving Kentucky. But it didn’t last: By 1948, the boom had waned, and many of Caudill’s coal-mining neighbors were left unemployed and struggling to get by.

Caudill traced the leaks in the schoolhouse roof to the advent of strip mining. Where traditional mines had dug downward in search of coal, this new technique used explosives to blast away a mountain’s face. Mining in eastern Kentucky was backed by broad-form deeds—exploitative legal agreements that let landowners keep their rights to the surface but granted mining companies all the mineral resources below. By destroying the land, strip mining rendered the rights that landowners retained functionally meaningless and allowed mining companies to extract wealth from the region while those who lived there saw little benefit.

Caudill’s diagnosis was in some ways accurate: Strip mining had ruined the environment, leaving communities vulnerable to catastrophic flooding, and the broad-form deeds had enriched mining companies at the expense of locals.

But he erred in his assessment of how it had impoverished the region. What made strip mining especially devastating was how the process disempowered the region’s labor unions, which for decades had used their unique political position as a check on the deeds, ensuring that a portion of the mines’ wealth remained in Appalachia. Strip mining required fewer workers than older methods of extraction. Thus, even as coal output soared, mining employment in Appalachia fell by more than half from 1950 to 1964. The unions withered. The region’s economy sank.

Instead of blaming the mining companies for cutting jobs and depressing wages, though, Caudill directed much of his ire at Appalachians themselves. Essential to his theory of Appalachian poverty was the notion that the mountaineer forebears who signed away their mineral rights were “putty in the hands of eastern capitalists” and that their descendants were both too dull to innovate and content to survive on welfare (those who were smarter or more ambitious, he wrote, emigrated from the mountains). Appalachians were, according to Caudill, at least a little bit dumb—pitiable, certainly, but responsible in part for their plight.

In April 1961, friends in Louisville sent a copy of Caudill’s manuscript to A. Whitney Ellsworth, then an associate editor at The Atlantic. Ellsworth liked what he saw. He fashioned Caudill’s submission into an excerpt, eliminating an extended riff on “America the Beautiful” from its opening and changing the headline from “The Appalachian Horror” to “The Rape of the Appalachians.” In February of the following year, Ellsworth sent Caudill proofs for review. The article was published in the magazine’s April 1962 issue. Buoyed by the article’s success, Ellsworth connected Caudill with Little, Brown, which developed his manuscript into a book, published the following year as Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area.

“All of a sudden, all hell broke loose,” Caudill’s son James told me, recalling the period following publication. “We had people coming from the ends of the earth, all over this country and a whole bunch of foreign countries as well.”

Readers were especially interested in the book’s lurid detailing of poverty. A spate of journalists and TV crews came to witness the desolation described in Night Comes to the Cumberlands, and Caudill served as their fixer, leading “poverty tours” that confirmed his assessments. He came to befriend the New York Times reporter Homer Bigart, whose front-page coverage of Appalachia’s plight brought Caudill’s book to the attention of staffers at the White House.

In April 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson helicoptered into Martin County, Kentucky, where, from the porch of an unemployed mill operator, he promoted his new slate of social legislation. Appalachia became the War on Poverty’s first front. The photographers and members of the press Caudill showed around dutifully extracted portraits of hardship from the mountains, fuel for Johnson’s initiatives. A Life photo essay centered on the region was titled “The Valley of Poverty.”

But Johnson’s proposals fell short of what Caudill had envisioned—a Tennessee Valley Authority–style program that would totally wean the local economy off coal. Highly skeptical of traditional welfare programs, Caudill told Michael Murphy, who wrote the text accompanying “The Valley of Poverty,” that “the agencies have turned all of eastern Kentucky into paleface reservations, changing sturdy mountaineers into human vegetables that come alive only at election time when they are trotted out to vote.”

His caustic assessment of his neighbors may have shocked admirers, but the same disdain whispered throughout much of Caudill’s work.

“As the more intelligent and ambitious people moved out of the plateau the percentage of mental defectives relative to the total population rose sharply,” Caudill wrote in Night Comes to the Cumberlands. “But such disability as they may suffer does not prevent them from procreating, and they beget great gangs of children who tend to inherit or soon to acquire the shortcomings of their parents and to become Welfare beneficiaries as soon as they are born.” (His most strident claims were largely absent from his writing for The Atlantic, though a 1964 article titled “The Permanent Poor” repeats his description of eastern Kentucky as a “paleface reservation.”)

Over time, the bitterness of his rhetoric only calcified. The War on Poverty sent billions of dollars to Appalachia, and by some estimates it reduced poverty in the region by 7.6 percent. Still, widespread poverty lingered, and to explain it, Caudill searched for the root of Appalachians’ plight in the personal qualities that he believed made them distinct from other Americans. In the 1970s, he became fascinated with “dysgenics”—the scientifically baseless claim that less intelligent people were “outbreeding” their smarter peers, driving down the overall quality of the gene pool. Convinced that dysgenics explained Appalachia’s predicament, Caudill contacted the Nobel Prize–winning physicist turned eugenics advocate William Shockley and invited him to Whitesburg; there, they and others patched together a plan to administer intelligence testing and offer cash bonuses to Appalachians who volunteered to be sterilized. It never took off.

Facing an advancing case of Parkinson’s disease, Caudill died by suicide in 1990.

In her flowing, floral gown, Stacy Kranitz was a difficult figure to miss. “She immediately caught my eye,” Derek Henry, now a friend of Kranitz’s, told me. The two first crossed paths at the 2012 Rainbow Gathering—an annual countercultural assembly—held that year at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where Kranitz’s dress had drawn a gaggle of admiring onlookers.

Her outfit, she told them, was inspired by Catherine Marshall’s 1967 novel, Christy, the story of a young woman who comes to Appalachia as a schoolteacher only to find her stereotypes of the region dismantled by the people she encounters (Christy was later adapted into a popular 1990s CBS drama). Henry pressed forward in the crowd. He knew Christy well; Cocke County, Tennessee, where he’s lived most of his life, served as the novel’s setting. Henry and Kranitz agreed to keep in touch, and eventually Kranitz traveled to Newport, Henry’s hometown.

CNN had recently published a series of Kranitz’s photos under the headline “Life in Appalachia”—but many Appalachians felt that the editors’ selected images, of cross burnings and snake handlers, reduced them to a stereotype, much as Life magazine had 50 years prior. “My advice to her was to lean into that controversy, to not run away from it, to not be afraid of it,” Henry told me.

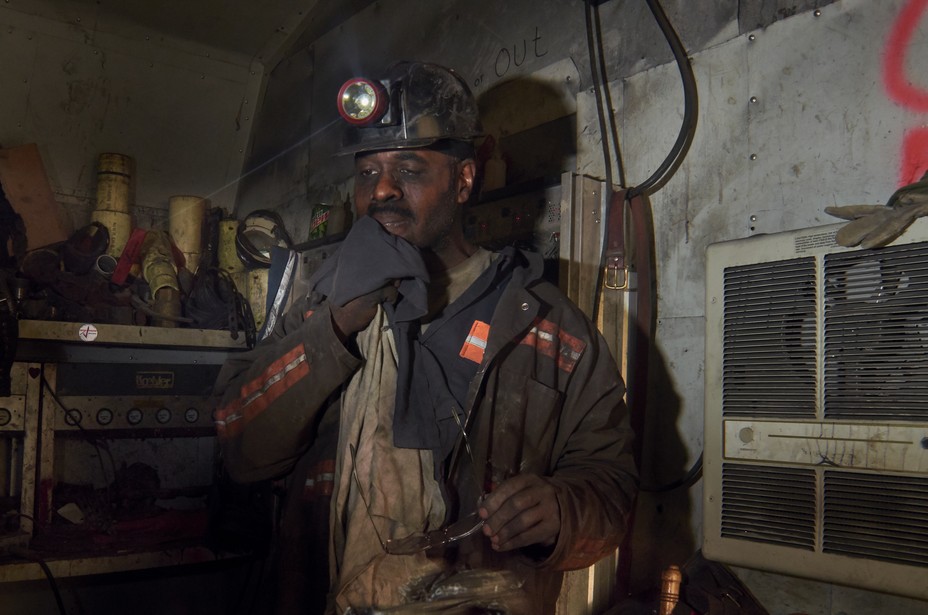

“There’s a lot of beauty here,” Henry said. “But hatred and backwardness—that is here too.” To counter Harry Caudill’s negative image of Appalachia with an overly sanitized one would be equally reductive—and too easy. Unlike “The Valley of Poverty,” Kranitz’s body of work isn’t interested in shaping a single narrative about the region. Her photos don’t sand down Appalachia’s rougher edges, but they don’t leer at them either.

Kranitz has remained close friends with many of the people she’s met in the region, several of whom, including Henry, appear in As It Was Give(n) to Me. “I’m one of her favorite models,” Henry joked.

“I’ve always respected Stacy for coming into some of the darkest corners of these areas and documenting whatever she sees from a modest perspective and with a completely open mind,” Colby Dotson, who is also a favorite model, told me. The photobook is dedicated to Dotson, Henry, and another of Kranitz’s friends.

Christy serves as an important touchstone for Kranitz’s work: Scattered throughout her book are a series of self-portraits in which Kranitz dresses as Marshall’s protagonist, reminding viewers who get the reference that, like Christy, she is an outsider, hampered by biases. Those who don’t, though, could easily assume that the floral-gown-clad Kranitz is a “genuine” Appalachian, wearing a dated dress simply because she’s been lost to time. That’s the point.

“They’re a ‘fuck you,’” Kranitz told me of the self-portraits. “You’re on this journey thinking that what I’m giving you is this very earnest perspective of this place,” she said, “but actually, it’s really just my fantasy colliding with the reality I’m experiencing.” In that collision, Kranitz often finds her views dismantled.

“That’s why I do this work,” Kranitz said, “to be completely undone by the people that I engage with.”