Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858, combination print, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

The pioneering photographer found himself thrown into infamy in 1858, with the creation of his combination print, Fading Away. Depicting a young girl awaiting an imminent death from consumption, while her mother and sister look on in doomed anticipation, her father turns away from the fated scene in profound sorrow, wiping the tears from his eyes while facing out over a balcony beneath a fittingly overcast sky. The piece is certainly striking, the dramatic effect of the tableau subtly heightened by the heavy curtains which hang in the image’s background, reminiscent of a stage play.

While death was something of an obsession for the Victorians, whose wealthy commonly practiced post-mortem photography, and hung paintings depicting the dead and dying upon their house walls, Robinson’s Fading Away did not garner the response that one might, not-unreasonably, assume. The piece was immediately condemned for delving too deeply into a subject that was immensely personal and private – despite the fact the whole scene was staged. This public reaction stands as a testament to Robinson’s unwavering vision as an artist, for he created a work so poignant, so viscerally striking, that it was treated as if it was an exhibited documentation of an actual death, and not purely artistic vision. However, not all response was of a negative nature, for Prince Albert – an avid amateur photographer himself, ordered a copy, and would go on to purchase other copies of Robinson’s work, and despite the controversary surrounding it, Fading Away also made him the most famous photographer in England.

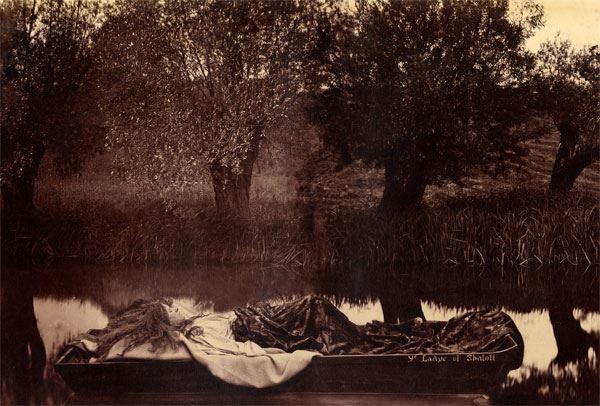

Henry Peach Robinson, The Lady of Shalott, 1861, toned albumen print from two negatives, Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford

Despite the fuss that Fading Away created, Robinson’s subsequent works, such as 1861’s The Lady of Shalott, and 1863’s Autumn, were highly praised by the public. However, Robinson was forced to close his studio in 1864 due to declining health. The years of being exposed to toxic photographic chemicals had taken its toll. He would continue to create his combination prints, but by the ‘scissors and paste-pot’ method as opposed to the more time-consuming darkroom technique. After relocating to London, he turned his efforts once again toward the world of publishing.

In 1869 Robinson published the photographic practice handbook, Pictorial Effect in Photography. This handbook would become the most influential English language work on photographic technique and aesthetics for decades. His subsequent writings on photography were widely distributed and translated, disseminating his artistic vision to the masses. His health now improving, Robinson opened a new photographic studio in Tunbridge Wells, and in 1870, became vice-president of the Royal Photographic Society.