This spring at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, male-physique enthusiasts can have their beefcake and try to eat it too. Dishing up much more than a hundred photographs – in addition to magazines, own albums and image sheets – the freshly opened exhibition ‘A Tricky Person is Very good to Find!’ is a feast for the eyes.

Titled after American actress Mae West’s well known quote, the exhibition spans 60 a long time of queer graphic-making, from svelte bathers to muscle hunks and scruffy punks. It is divided into 50 percent a dozen sections, which map out subcultural territories of the British cash, from Hampstead Heath to Portobello and Euston.

‘In the early portion of the 20th century, homosexuality was illegal,’ the exhibition curator Alistair O’Neill notes as we stroll through the gallery’s child-pink partitions. Inspite of the 1955 Wolfenden Report – which proposed the depenalisation of homosexual acts involving consenting grown ups – and the subsequent 1967 Sexual Offences Act – which marked the partial decriminalisation of gay sexual intercourse – Britain’s obscenity laws remained a sizeable obstacle for the creation of homoerotic imagery. ‘Representations of the male nude came below sizeable scrutiny and the capability for queer men to seem at other gentlemen in states of undress was quite constrained,’ continues O’Neill, who teaches Manner Historical past and Idea at London’s Central Saint Martins.

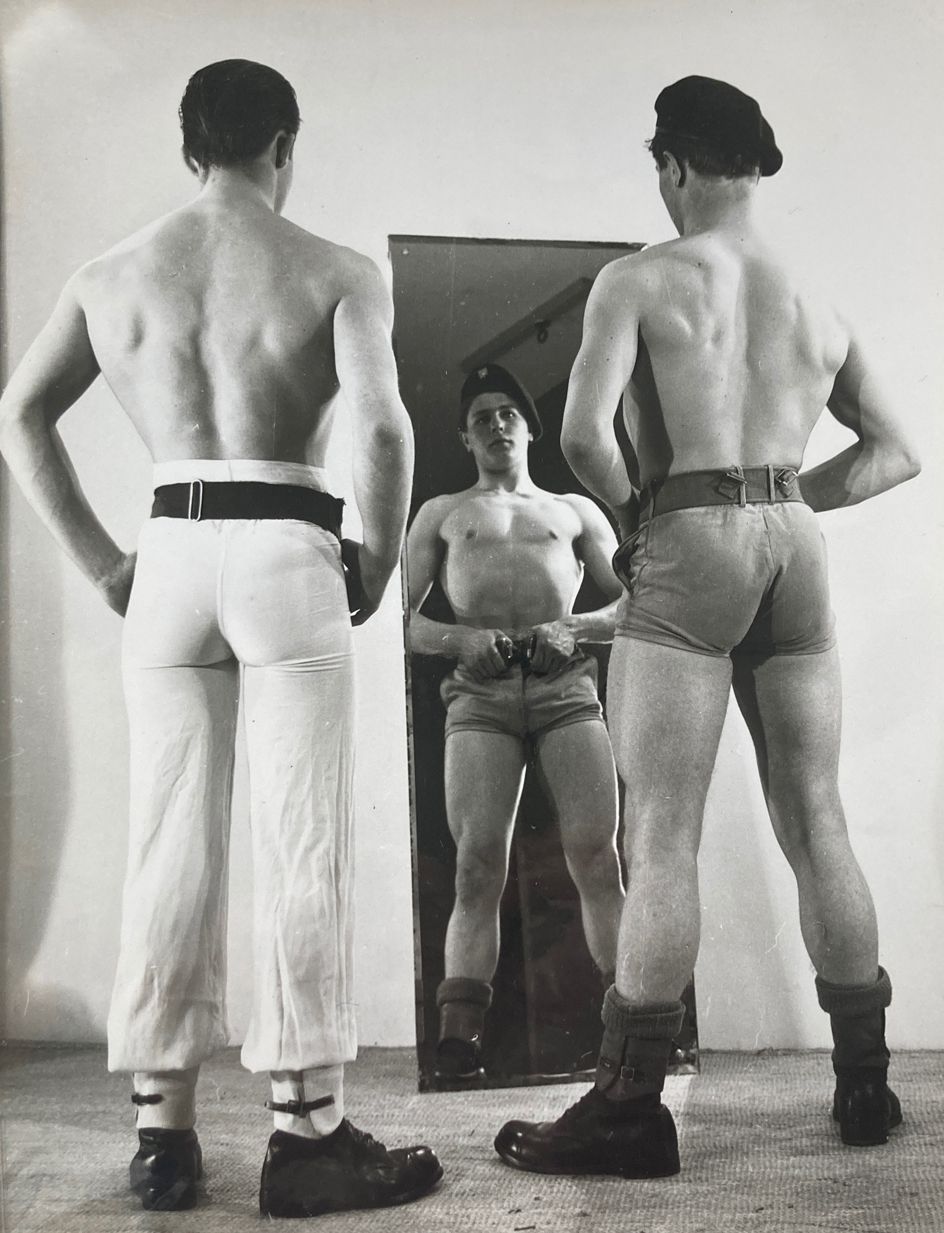

Angus McBean, David Dulak, 1946

(Image credit score: Courtesy Rupert Smith Assortment)

The exhibition begins strongly with a hardly ever observed collage collection by British painter Keith Vaughan, dated from 1933. It characteristics slice-out photos of thong-wearing sunbathers taken by the then-21-yr-outdated artist at Highgate Men’s Pond. Superposed with textual things in excess of monochromatic olive-inexperienced backgrounds, the images are compiled in a diary-design and style photobook that is on exhibit powering a glass cabinet, whilst enlarged prints of personal pages are reproduced on a wall.

‘He’d just acquired a Leica digicam and turned his bed room in his mother’s house in West Hampstead into his dim room,’ O’Neill recounts. ‘He wouldn’t have been ready to print these commercially since of the mother nature of the images.’ At after scenic and suggestive, they enjoy with contrast and repetition in remarkably modernist ways that prefigure factors of Richard Hamilton’s early Pop Art. Apparently, the existence of jockstraps in the pictures suggests that the famed undergarment did not become a gay image in 1950s The united states with the introduction of journals these types of as Physique Pictorial, as is normally assumed. (For supporters of the latter, a unusual posing pouch lovingly crafted by its publisher Bob Mizer’s mother is on display in the adjacent annexe room.)

Basil Clavering, (Royale, Hussar, Dolphin). Mail get Storyette print, late 1950s

(Picture credit history: Courtesy Rupert Smith Collection)

It’s not all about sex: many performs in the display are imbued with an irresistible camp excellent, as well. Main among them, the 1950s ‘storyettes’ – catalogue photo sheets assembled into a narrative – display their makers’ imaginative use of humour. Conceived to discreetly market erotic prints to get by mail, storyettes were being initiated by sailor-turned-cinema owner Basil Clavering from his basement studio in Pimlico. To stay away from scrutiny, Clavering assembled the photos like movie stills, orchestrating comical scenarios in which armed service males are observed progressively undressing, flexing their muscle tissue in entrance of a mirror and ultimately ironing each individual other’s uniforms in the nude. ‘It’s sort of seaside postcard humour,’ O’Neill laughs, ‘or like a drag pantomime.’

At moments, the exhibition’s desire to illustrate a person community’s attempts to develop and flow into radical visuals eclipses important problems such as consent and exploitation. For occasion, 1930s erotic illustrations or photos of doing work-class guardsmen exchanging sexual intercourse and consumerist pleasures for money avenue and intimate portraits of 1980s punks catfished in the streets of King’s Cross underneath the pretence of a false Vogue campaign, and lists of models’ names categorised by race all place to complex energy dynamics that the present does small to tackle or contextualise.

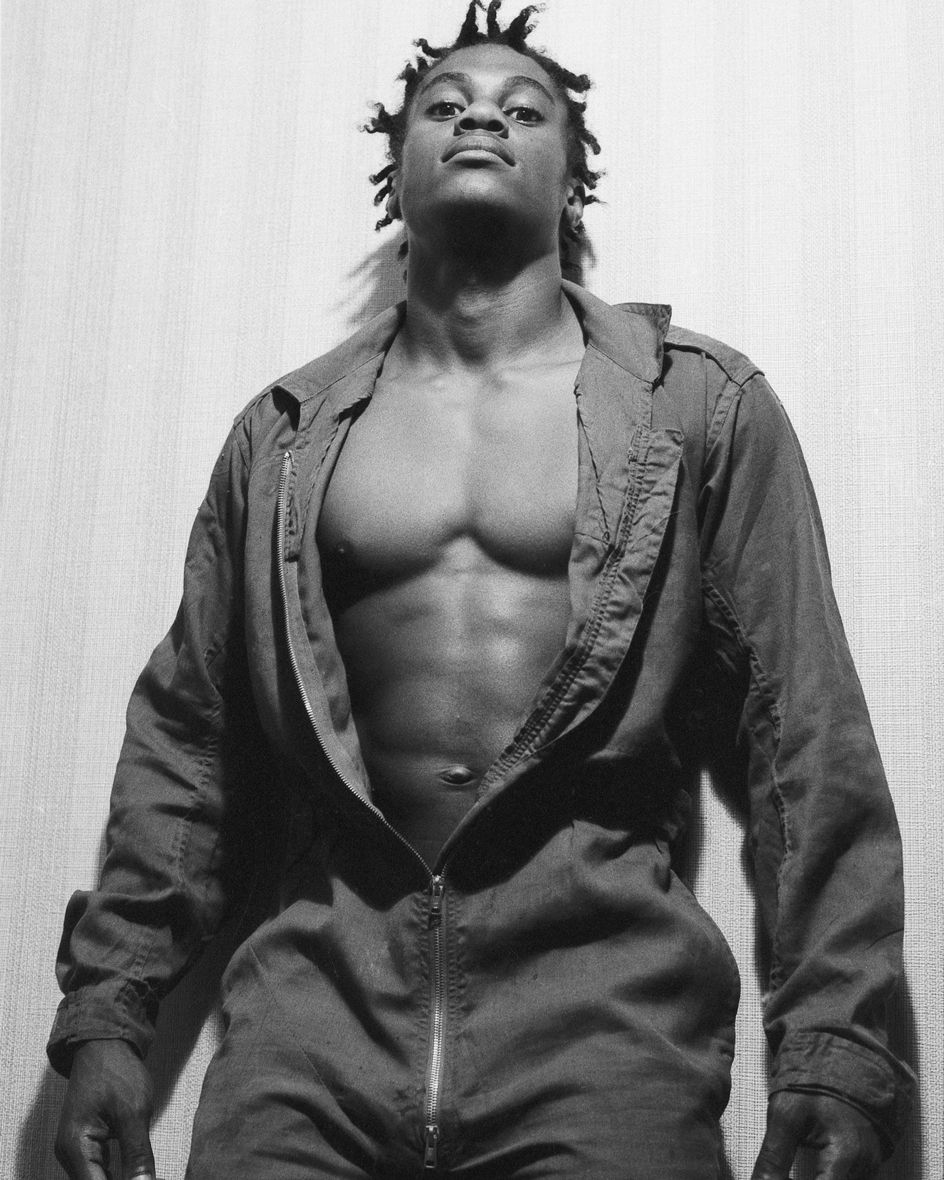

(Image credit history: Courtesy of the Michael Carnes Selection)

Luckily, the final exhibit delivers some a lot-wanted nuance to this narrative with a glimpse into the Brixton Art Gallery’s growth. Opened in 1983 under a railway arch, it was run by an artist collective such as the likes of Ajamu X, Franko B and Dude Burch, whose queer and intersectional get the job done was mainly excluded from mainstream exhibition spaces. A single arresting portrait by the late Nigerian photographer Rotimi Fani-Kayode – a distinguished figure of the Black British Artwork scene and founding member of the activist artwork organisation Autograph – exhibits a Black nude model gazing at the camera by a Venetian lengthy nose mask, his genitals coated in gold paint. Titled The Golden Phallus, the perform was designed in 1989 to tackle colonial stereotypes in the weather of the Aids disaster, namely Robert Mapplethorpe’s fetishist depiction of Black male nudes.

‘A Challenging Person is Very good to Discover!’ is a delectable present that compellingly traces the proliferation of an normally undermined visible subculture. Delight in it when it’s scorching.

‘A Tricky Person is Excellent to Discover!’, right until 11 June 2023, The Photographers’ Gallery, London. thephotographersgallery.org.uk (opens in new tab)