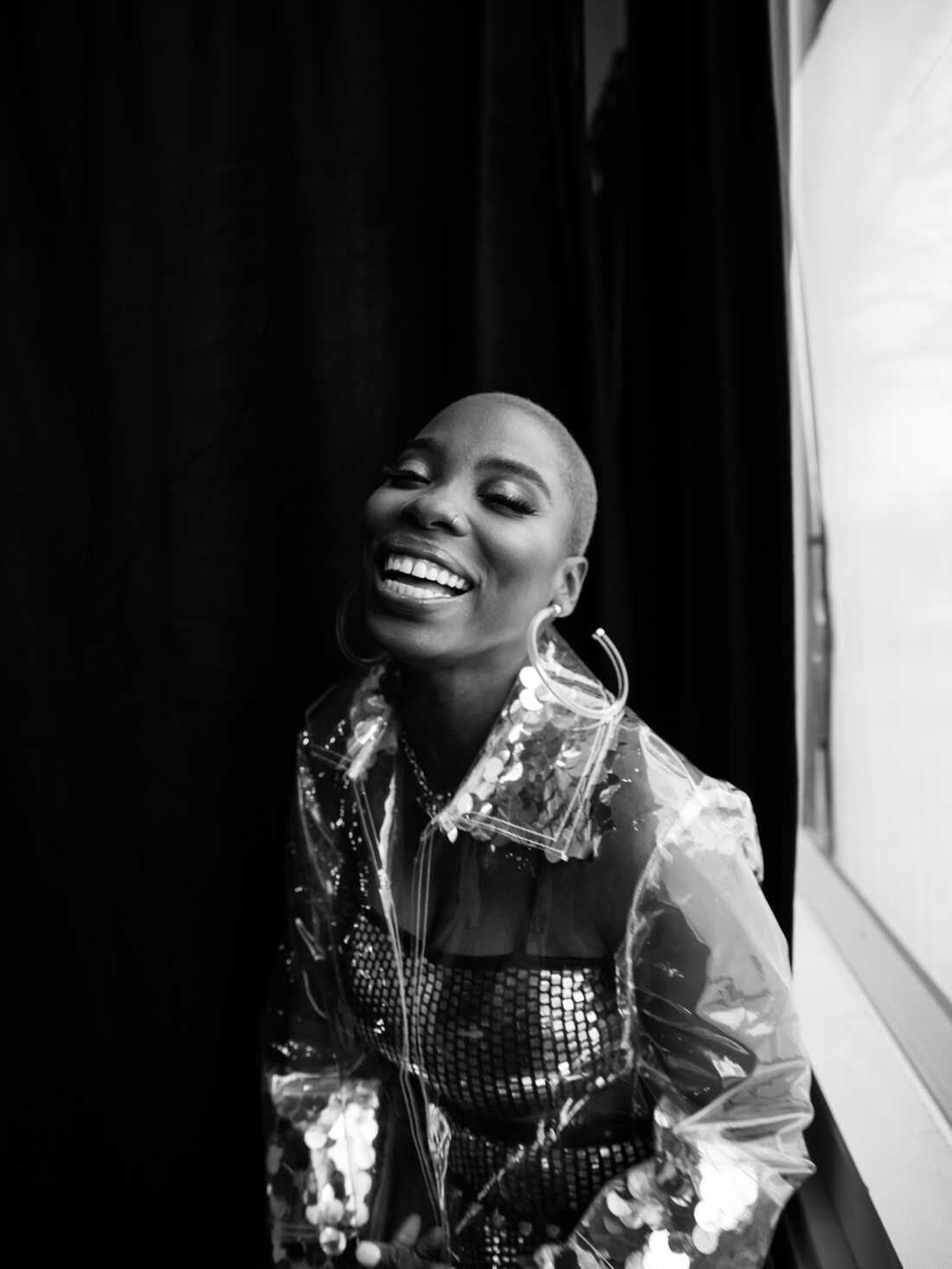

“I want to see more opportunities for women who have a message, who are dark-skinned,” says Jessy Wilson, whose uplifting “Keep Rising” with Angélique Kidjo closes the historical epic The Woman King.

Mary Caroline Russell

hide caption

toggle caption

Mary Caroline Russell

“I want to see more opportunities for women who have a message, who are dark-skinned,” says Jessy Wilson, whose uplifting “Keep Rising” with Angélique Kidjo closes the historical epic The Woman King.

Mary Caroline Russell

The Woman King — director Gina Prince-Blythewood’s historical epic starring Viola Davis about a mighty army of West African warrior women protecting their kingdom — is only the second film with a Black woman director to open at number one at the box office. The film’s renown means that millions have had a chance to hear the song that plays over its closing credits, but what’s received considerably less attention is the story of life-altering triumph tied to that undaunted pop anthem, “Keep Rising.”

Jessy Wilson wrote and recorded it with producer Jeremy Lutito in the studio behind his East Nashville, Tenn. home during the summer of 2020. She barely touched a microphone after that, soon stepping away from songwriting altogether. What drew her back one day in early October to that same, small studio space — and to music — was the chance to truly embrace the song’s role in a powerful piece of filmmaking. Without a label budget behind her, she’d decided to lay down a regally deliberate, acoustic version for a simple, live-looking music video. “After all this time, I hope I’m like a pro, that it’s like riding a bike,” Wilson shared after arriving on site and stowing her bag.

She certainly seemed in her element that day on the shoot, not only the lead performer who knew her instrument and how to apply it to the supple insistence of the verses and the chorus’ more inflamed exhortation, but the one steering the backing vocal trio’s arrangement, too. Once she got the vocal takes she was looking for, finished lip syncing for the videographers and took a seat on the same couch where she’d come up with “Keep Rising,” she was a compelling narrator.

YouTube

The decision to briefly give up music was a consequential one for Wilson. She’s no dabbler. At age 8, she’d already convinced her mom and an agent that she had the vocal ability, stage presence and drive to begin auditioning for off-Broadway roles. While attending LaGuardia, the Fame-famous Manhattan performing arts high school, she lied about her age to land a regular café gig. “They all thought it was weird,” she recalled, “like, ‘Why does she come with her mom every weekend?’ Eventually I told them the truth, but for a while, I just told them that I was a student at NYU, because I really wanted that experience.”

She was hungry to learn the studio side of her craft when John Legend hired her as a backup vocalist right after high school. “I think I had only been singing with him for, like, four weeks. And I said, ‘Can I come with you to the studio, please? I’ll be a fly on the wall. I won’t make a sound. I just wanna come,’ ” Wilson said. “He was like, ‘Yeah, absolutely.’ “

That’s Wilson supplying some resplendent, cooing echoes on Legend’s bossa nova-tinged 2006 track “Maxine.” She got into songwriting with his encouragement, eventually supplying cuts to other major R&B stars. Wilson thought she might become one of those herself, but kept coming up against colorism in the industry: “Being a dark-skinned Black woman, you know, being told that that wasn’t marketable, being told that that’s not worldwide, being told that no one would really be able to relate to me because of my complexion.”

“That was a concept that was very new to me, because in my home, my mother and my father taught me to love my complexion, to love my Blackness, to love my features that look like African features,” she went on. “It was a rude awakening when I realized that that isn’t the worldview and that somehow Black people are true victims of white supremacy when it comes to how we view ourselves, even in the mirror. When you have so much inside of you, that’s very painful as well, because you’re waiting for someone to give you that [professional] shot, and you’re waiting for someone to see you in that way [as an artist].”

After accompanying Legend to Nashville on a songwriting expedition, Wilson decided to give the city a try, relocating in 2013. In writing circles there Wilson was introduced to white musical partner Kallie North, and their soul-steeped, roots rock duo Muddy Magnolias was a revelation to a country-adjacent scene that made more room for Black musical influence than Black music-makers. “Those first two months of living here,” said Wilson, “I circled Music Row over and over, and I said, ‘God make me a pioneer.’ “

With Muddy Magnolias, Wilson finally got the record deal she’d been working for, a success she thinks was twofold. “The [vocal] blend was unmatched. It does something to the heart when you see a Black girl and a white girl up there singing in harmony, what it means to the spirit,” Wilson said. “But then also, you’ve got to think about the business side. It wasn’t a gimmick to us, but I think the industry found it easy to latch on to.”

Country singer-songwriter Brittney Spencer took note of the mark made by her Black predecessor back when she was a health food store employee who routinely filled Wilson’s juice orders, and recently called her to tell her so. “The opportunities that a lot of artists like me are able to get right now, I think, is because little by little people have been sowing seeds,” Spencer observed during a separate interview. “And even if this space wasn’t necessarily ready five, seven years ago, man, I was there and I watched it and I didn’t forget.”

When Muddy Magnolias broke up, Wilson started finding her voice as a solo artist on the sensually sophisticated, atmospheric side of rock and soul with the Patrick Carney-produced album Phase. She wanted to complicate the perception of her as “just this big singer.” “Phase gave me an opportunity to get quiet,” Wilson reflected. “People underestimate the power in getting quiet. I made an intentional decision to never open up my voice past a certain place on my album, because I had been singing full out my whole life and I wanted to hear the subtleties in my voice on record. … I wanted people to hear what I had to say.”

Around that same time, Tyler, the Creator tracked Wilson down on social media, urging her to sing on his album IGOR; he hadn’t been able to get her voice out of his head since he heard it billowing through “Maxine.” But those professional landmarks gave way to a string of personal losses. Wilson’s beloved grandmother died, and her New York healthcare worker dad barely survived COVID-19 in the early days of the pandemic. Then she and her husband lost a pregnancy.

“Unfortunately, after four months, we lost our child,” said Wilson. “It felt like I was just down in a hole. I kept looking for things to grab on to, but nothing was pulling me out. It’s even hard to really communicate or even think about those times, because the despair was just…” She trailed off, unable to find sufficient words.

In her compounded grief, it grew difficult for Wilson to deliver the songs she owed her publisher. One that she did submit was “Keep Rising.” “When I wrote the song, I was talking to Black people,” she explained. “There’s a part of the lyrics that I’m also talking to myself about myself: ‘Been marching so long. How far is it to get to where we’re going?’ Like, how long do we have to wait in America? How long does Jessy have to wait? When will we be seen as enough? When will I be seen as enough?”

At the time, Wilson didn’t have much hope that anything would come of that song, or any others she wrote. She lost her publishing deal in early 2021, and turned to making visual art. But on what would’ve been her baby’s 2022 due date she received big news. The director of The Woman King, Prince-Bythewood, had initially envisioned Terence Blanchard’s score soundtracking the entire film, but her search for just the right music to carry the audience out of the closing scene had led her to “Keep Rising.”

Sent a collection of unreleased tracks to listen to, Prince-Bythewood found in Wilson’s “exactly what I wanted the audience to feel. It makes you stand up and move. It was as if it was written for the movie.”

“When I wrote the song, I was talking to Black people,” Wilson says of “Keep Rising.”

Mary Caroline Russell

hide caption

toggle caption

Mary Caroline Russell

“When I wrote the song, I was talking to Black people,” Wilson says of “Keep Rising.”

Mary Caroline Russell

“One of the things I’m most excited by,” she added, “is I love hearing Jessy’s story and who she is as an artist, where she was at the moment that this call came. I love that we have the power to elevate artists who deserve it. And Jessy, her voice, the depth that she brings to her work, absolutely deserves this opportunity.”

Prince-Bythewood asked Wilson to adapt two lyrics to the film’s time period and agree to a feature from legendary singer Angélique Kidjo, who’s from the region where the film takes place, then known as the kingdom of Dahomey. “She is the first lady of Benin, essentially,” the director notes, “so important to the empowerment of girls in Africa, an incredible activist. I wanted her voice and I wanted to kind of bridge the two, America and Africa.”

Wilson didn’t at all mind making those adjustments. “I feel so connected to the intention in their mission for what they want this movie to accomplish in our industries,” she said with serene conviction. “I want to see more opportunities for women who have a message, who are dark-skinned. And so if I can somehow open any doors, then I feel like I can hold on to that, the possibility of that, as my newfound purpose.”